As the automotive industry accelerates towards electrification, the question of what happens to used vehicle batteries has become more urgent than ever. From traditional lead-acid batteries used in millions of cars to advanced lithium-ion packs powering electric vehicles (EVs), recycling plays a pivotal role in the sustainability and resource security of modern transport.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), demand for critical materials such as lithium, nickel, and cobalt is expected to increase up to tenfold by 2030. Recovering these materials from end-of-life batteries is therefore not only an environmental imperative but also an economic necessity.

In this article, we explore how automotive batteries are recycled, what materials are recovered, and how today’s “dead” batteries are helping to power the cars of the future.

Why Battery Recycling Matters

Battery recycling is about far more than waste management — it underpins the circular economy of the automotive and energy industries. Key reasons include:

- Resource conservation: Both lead and lithium are finite resources. Recycling reduces the need for new mining and helps stabilise supply chains.

- Environmental protection: Improper disposal of batteries can release toxic materials such as lead, sulphuric acid, or electrolyte salts into the environment.

- Energy efficiency: Recycling lead and lithium consumes significantly less energy than extracting them from raw ore.

- Economic value: Recovered metals such as lead, copper, nickel, and cobalt are high-value commodities that can be reused in new batteries.

According to the Battery Council International (BCI), lead-acid batteries are the most recycled consumer product in the world, with recovery rates exceeding 98% in Europe and North America.

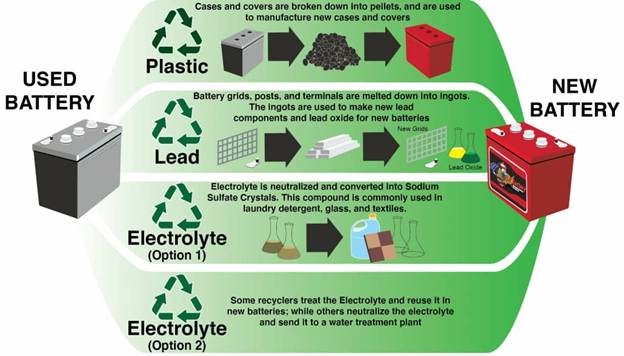

How Lead-Acid Battery Recycling Works

Despite the rise of electric vehicles, lead-acid batteries remain the most common automotive energy source — powering starters, lighting, and ignition (SLI) systems. Fortunately, they are also the most successfully recycled.

Step-by-Step Recycling Process

- Collection and Transportation

Used batteries are collected from retailers, garages, and recycling centres. Strict transport regulations ensure containment of hazardous materials. - Battery Breaking

At specialised recycling plants, batteries are crushed in hammer mills. Plastic, lead, and acid are separated by density and filtered for further processing. - Material Recovery

- Lead: Smelted in furnaces to produce pure lead ingots or lead oxide for new battery plates.

- Plastic (polypropylene): Cleaned and reprocessed into new battery cases.

- Sulphuric acid: Neutralised and converted into sodium sulphate, used in detergents and fertilisers.

- Closed-Loop Manufacturing

Nearly all recovered materials are used to manufacture new batteries — a perfect example of a closed-loop system.

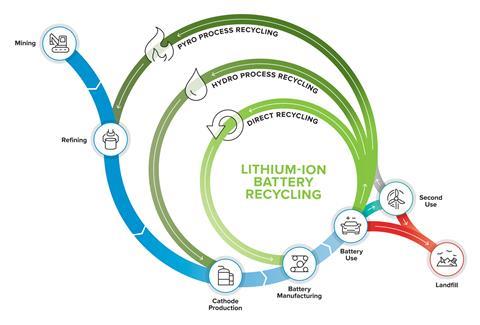

The Rise of Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling

While lead-acid recycling is well established, the challenge now lies in recycling lithium-ion batteries from electric and hybrid vehicles. Unlike lead-acid batteries, EV batteries contain heavy metals including lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, aluminium, and graphite and hazardous materials. If disposed of in landfill, they can leach toxic substances into soil and groundwater. Recycling significantly reduces the carbon footprint associated with EV manufacturing. According to a study cited by the Faraday Institution, using recycled materials can cut the CO₂ emissions of battery production by up to 50% compared to using virgin materials.

The EV Battery Recycling Process: A Technical Breakdown

Recycling an EV battery is a complex, multi-stage operation that requires precision engineering and stringent safety protocols, adhering to standards such as IEC 62660 series, UN 38.3 on reliability and abuse testing for battery cells.

Stage 1: Safe Deactivation and Disassembly

- Diagnosis and Discharge: Upon arrival at a certified facility, each battery pack is diagnostically tested. The remaining energy is then safely discharged to a zero-voltage state.

- Manual Disassembly: Trained technicians, using specialised insulated tools, dismantle the battery pack into its constituent modules and, further, into individual cells. This step is often manual due to the vast variation in battery pack designs from different manufacturers. The goal is to separate plastics, wiring, and control electronics for their own dedicated recycling streams.

Stage 2: Hydro- and Pyrometallurgical Processing

Once the cells are liberated, they undergo one of two primary recovery processes, often in combination.

- Pyrometallurgy (Smelting): This is a high-temperature process where battery cells are fed into a furnace. The organic components (electrolyte, separators) burn as a source of energy, while the metals form a mixed alloy (cobalt, nickel, copper) and a slag layer (containing lithium, aluminium, and manganese). While effective at recovering the more valuable cobalt and nickel, pyrometallurgy traditionally had lower recovery rates for lithium. Modern facilities, however, can now recover lithium from the slag, significantly improving overall yield.

- Hydrometallurgy (Leaching): This process involves shredding the battery cells and then using aqueous chemical solutions to leach the valuable metals from the resulting “black mass” – a powder containing the anode and cathode materials. Through a series of precise chemical precipitation and solvent extraction steps, individual elements such as lithium carbonate, cobalt sulphate, and nickel sulphate are separated with high purity. Hydrometallurgy is renowned for its high recovery rates, often exceeding 95% for key metals.

Leading recyclers are increasingly adopting hybrid models, using pyrometallurgy for initial processing and hydrometallurgy for final purification, maximising material recovery.

Second-Life Applications: From Cars to Storage

Before EV batteries are recycled, many undergo a second life phase. Although no longer suitable for traction use, they often retain 70–80% of their original capacity — ideal for stationary energy storage.

Common second-life uses:

- Grid balancing for renewable energy integration

- Home energy storage systems for solar panels

- Backup power for telecom and data centres

- Commercial microgrids in industrial facilities

For instance, Nissan repurposes used Leaf EV batteries to store solar energy at its manufacturing plants, while BMW uses retired i3 batteries in energy farms supporting its Leipzig factory.

These applications extend battery life by several years before final recycling, maximising resource efficiency and reducing carbon footprint.

Environmental and Economic Benefits

Environmental

- CO₂ Reduction: Recycled lithium emits less CO₂ than mined lithium carbonate.

- Water Savings: Hydrometallurgy uses < 10 % of water vs. mining (Redwood Materials, 2024).

- Biodiversity: Eliminates sulphuric acid runoff from cobalt mines.

Economic

- Cost Parity: Recycled cobalt priced at €22–25/kg vs. €30–35/kg mined (London Metal Exchange, Nov 2025).

- Supply Security: EU reduces reliance on DRC (68 % global cobalt) and China (65 % refining).

Challenges and Technological Innovations

1. Complex Chemistry and Design

Different manufacturers use varied chemistries (e.g., NMC, LFP, NCA), complicating automated recycling processes. Current battery packs are not designed for easy disassembly. Manufacturers are now working on concepts like glue-less pack designs, standardised cell formats, and digital battery passports (as mandated by the EU Battery Regulation) that will provide recyclers with vital information on chemistry and construction.

2. Economic Viability

The economics of recycling are sensitive to the market prices of cobalt and nickel. Innovations in direct cathode recycling—where the cathode material is rejuvenated rather than broken down to its elemental constituents—promise even lower costs and energy consumption.

3. Safety and Handling

Damaged or high-voltage batteries pose risks of thermal runaway or fire if improperly handled.

4. Regulatory Framework

The EU’s Battery Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 mandates minimum recycled content (e.g., 16% cobalt, 6% lithium, 85% lead by 2031) and traceability requirements — a major driver for technological innovation.

5. Emerging Solutions

- Automation and robotics for safer disassembly

- Water-based hydrometallurgy to reduce environmental impact

- Design for recycling principles encouraging modular, standardised battery architectures

As these innovations mature, recycling efficiency and recovery rates will continue to rise, supporting a truly circular automotive economy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Conclusion

Battery recycling is no longer an afterthought — it is a cornerstone of sustainable mobility. The era of linear battery lifecycles—mine, refine, use, discard—is over. From traditional lead-acid systems to advanced lithium-ion EV batteries, recycling transforms waste into valuable raw materials that can power the next generation of vehicles.

With advancing technology, robust regulation, and growing industry investment, tomorrow’s cars may quite literally be powered by the remnants of yesterday’s batteries — a circular revolution driving us towards a cleaner, resource-efficient future.

References

- Battery Council International (BCI) – Battery Recycling Facts & Data, 2024.

- Exide Technologies – Closed-Loop Battery Recycling Process, 2024.

- International Energy Agency (IEA) – Global EV Outlook 2024, 2024.

- European Commission – Battery Regulation (EU) 2023/1542, Official Journal of the European Union, 2023.

- Umicore Battery Recycling Solutions – Hydrometallurgical Process Overview, 2024.

- Nissan Motor Corporation – Second-Life Energy Storage Projects, 2023.

- Bosch Automotive Handbook, 11th Edition – Battery Manufacturing and Sustainability, 2023.

- Li-Cycle Holdings Corp. – Lithium-Ion Recycling Technology White Paper, 2024.